TurningArtist Yvette Kaiser Smith’s work always involves numbers. Using grids and simple shapes, she creates geometric abstractions that act as tools for visualizing numerical sequences derived from numbers like pi and e.

Working with both crocheted fiberglass and laser-cut acrylic, Yvette’s work is extremely diverse both in look and process. However, all of her pieces work towards the same goal of mapping and visualizing numbers, a fact that thematically unifies her large body of work.

We interviewed Yvette to get a closer look into how she goes about creating her various works.

Can you tell us about your journey to becoming a professional artist?

When I was young, I liked drawing. All through high school, I doodled on all my paper textbook covers and my friends’ textbook covers. Art was not a priority in the school system that I attended, and home life did not allow the opportunity for developing art skills. College seemed out of reach. In my mid-twenties, I started taking classes at one of the Dallas County Community Colleges (DCCC). After sixty-plus hours of foundation and accounting classes, I realized that accounting was not me. I took an intro to design class during summer which was combined with intro to drawing because not enough students signed up. A door opened and with the force of a quasar, a light lit up inside of me. I marveled, look at what I can do, and wow how it makes me feel.

I switched to the DCCC campus that specialized in fine and commercial art, which in the early 1980s did not involve computers. After a year of classes, I joined a semester in Rome offered by the same campus. Curiously, in all my independent study projects, I chose to focus on sculpture. In Italy, my artist identity began to coalesce. Then life happened and my education paused. A couple of years later, I made some bad paintings and applied to Southern Methodist University with hopes of a scholarship. It was the first year SMU offered a DCCC transfer student scholarship. I received two and a half years of tuition and fees plus multiple small grants along the way.

On day one, the art chair said, hey, we have a new sculpture professor, take a sculpture class. From that moment on, learning and making art has been the center of my universe. My BFA focused on sculpture and photography, and although I had very little experience with painting, I had the privilege of a fellowship to Yale Summer School of Art in Norfolk, Connecticut which was anchored in painting with other 2D media as supports to the painting studio. While finishing my BFA studies, I discovered that my lane was one of reduction and abstraction. I began to learn that every material and its process has its own unique language, its own specific ways to articulate my conceptual priorities and I began to learn how to use this specificity to create endless possibilities within minimal expressions.

Upon graduation in December 1990, I married and followed my partner to Chicago. I received an MFA in sculpture in 1994 from the University of Chicago, also on a full ride. The most significant gift from the U of C study was that I learned how to think and I began developing the way I now approach art-making. The privilege of scholarships meant no student loans which allowed more studio time and more leeway to juggle life to allow more studio time. Can you tell us about your work?

Can you tell us about your work?

Using grids and the repetition of simple geometric shapes, I create works that map and visualize numerical values like pi, e, prime numbers, and Pascal’s triangle.

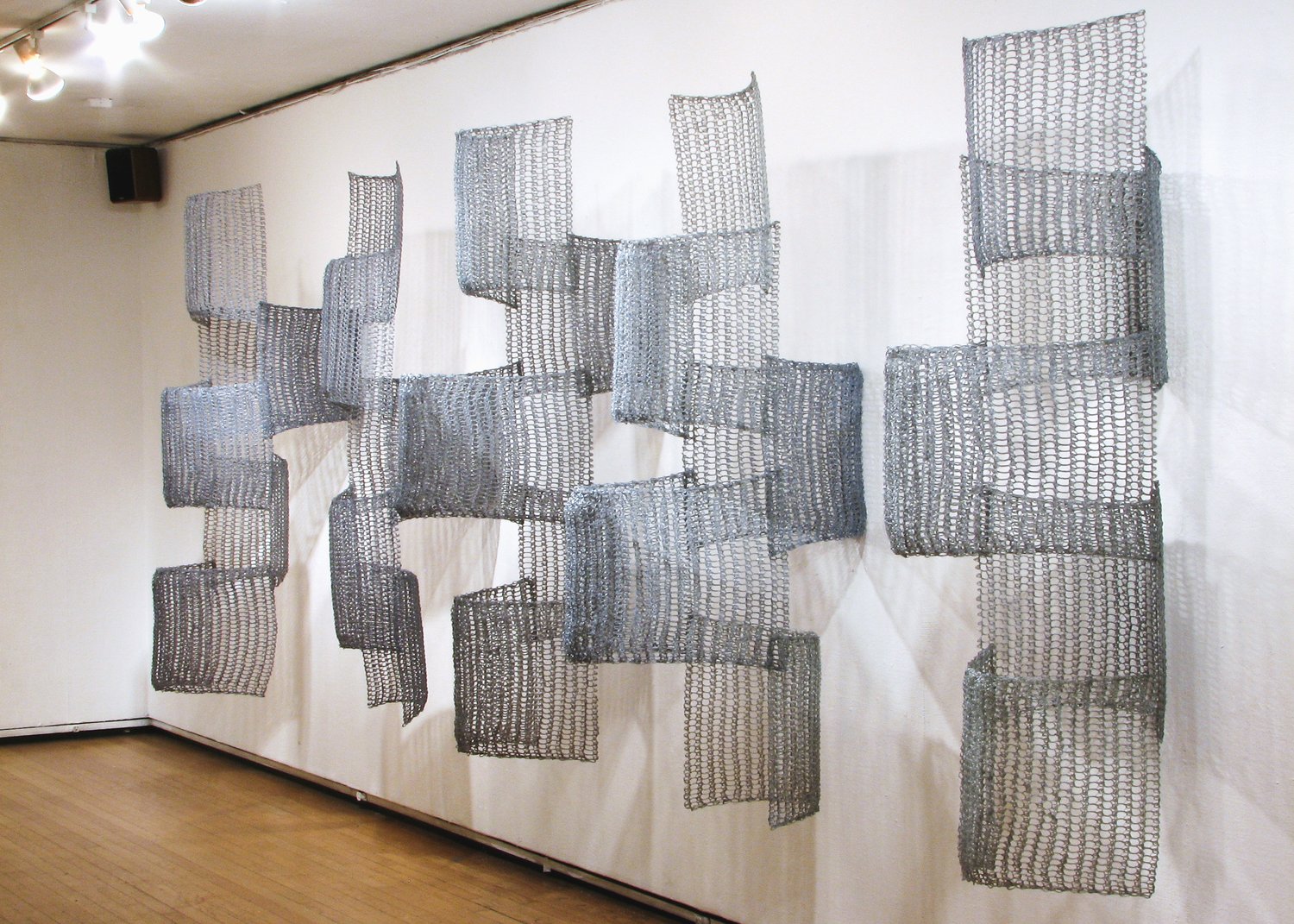

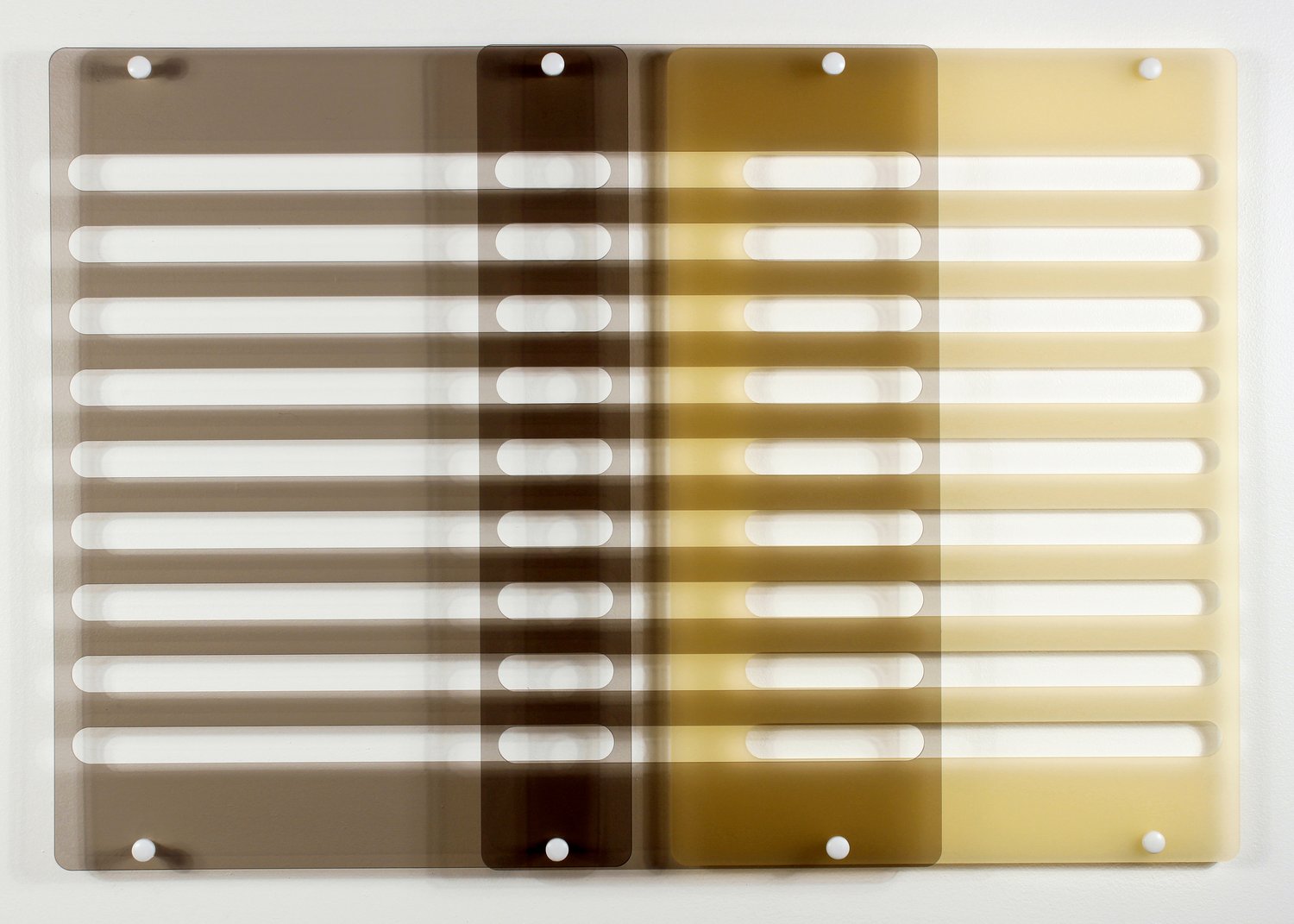

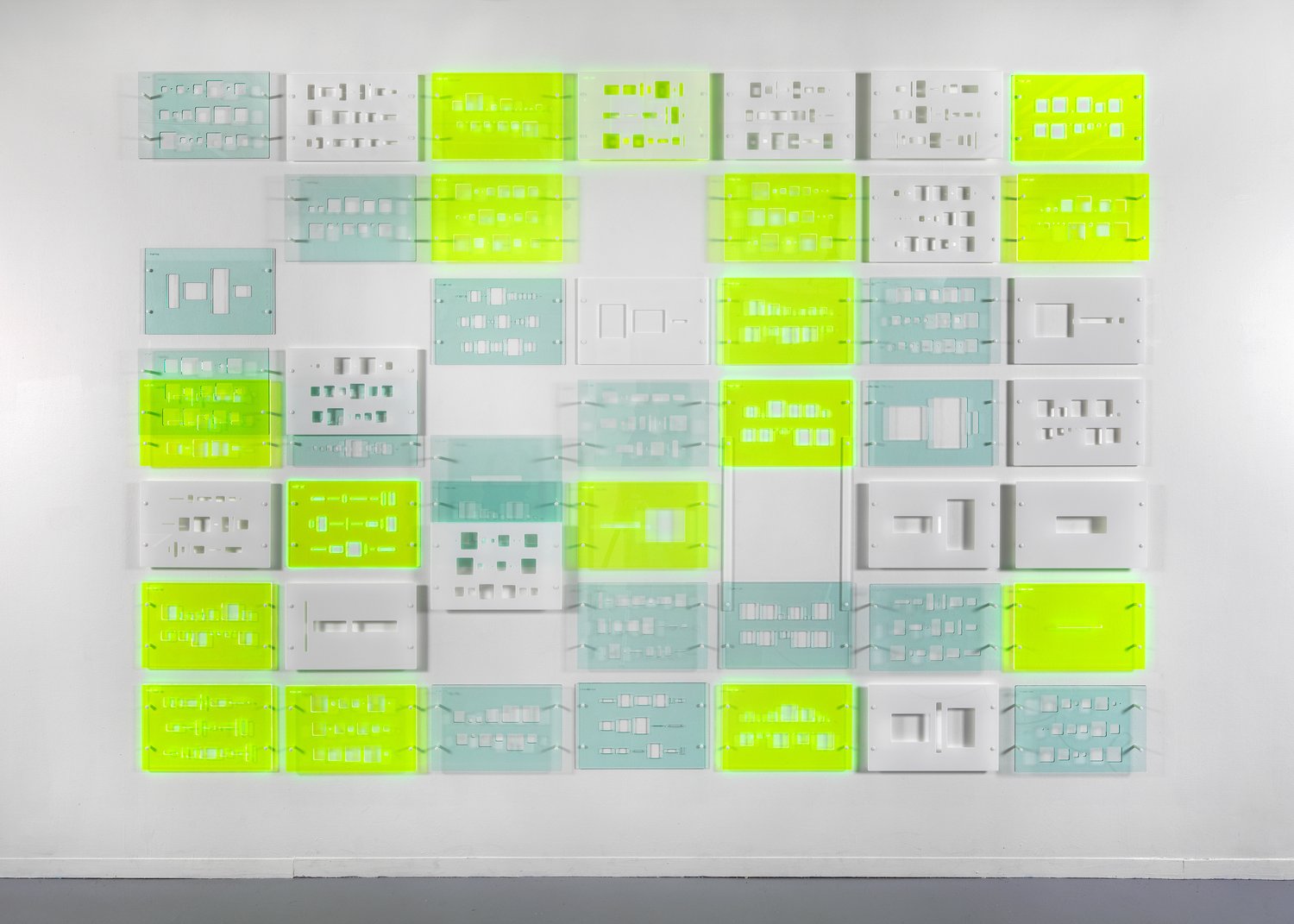

The majority of my past works are wall-based, geometric, crocheted fiberglass constructions. I create my own fiberglass cloth by crocheting continuous strands of fiberglass into flat geometric shapes. These are formed and hardened with the application of polyester resin and the use of gravity. In 2016, I was introduced to a laser cutter and have since focused on developing a body of wall-based works, using laser-cut acrylic sheets separated by vinyl spacers. Here, simple geometric shapes, panel placement, cut-outs, and engraved lines plot numerical values.

Every material has its own way of articulating specific things. Crocheted fiberglass and laser-cut acrylic, as completely different material processes, lend themselves to different ways of visualizing digits in their own respective language. Combining the language of numerical values with the language of crocheted fiberglass lent itself to a limited number of math-mapping systems. Combining the language of numerical values with the language of laser-cut acrylic sheet, still in its infancy as exploration, promises new challenges and many more possibilities. Also, for many of the mapping systems that I develop, because no sequence in pi repeats, I can create an infinite number of unique works.

I spent over 20 years creating large works by crocheting fiberglass that was formed by adding polyester resin, a labor-intensive process that engaged my hands at every stage. The laser-cut work has almost completely removed my hand or the sense of my hand from the final product. All the 2016, 2017, and 2018 work with acrylic sheet was designed in Photoshop, plotted in Illustrator, and created entirely on a laser cutter. I am now beginning to explore different ways to bring my hand back into the work.

An accumulation of iPhone snapshots of Chicago streets, framed as geometric compositions observed while sitting in traffic, has led me to create a new body of work that combines digital prints on transparency film with laser-cut acrylic structures. Now part of my material/process toolbox, I plan to explore ways to combine photographic images printed on transparency film with the geometric acrylic works.

Can you tell us about your process?

Crocheted fiberglass:

To determine the form, I visualize ideas in quick sketches, based on different number sequences. Drawings get scanned and printed in multiples as templates for color play, in colored pencils, also based on number sequences. Using continuous fiberglass roving and a standard 6mm crochet hook, I create my own fiberglass cloth by crocheting flat geometric shapes. I then build a temporary wooden jig for hanging or draping. I pre-mix colored resin, in 16 to 24 ounce cups, for the entire project, to ensure color continuity, using resin dyes and hard finish polyester resin. Hard finish resin is polyester resin with 5% styrene wax which rises to the surface as resin hardens. This gives the product a smooth, hard finish which is easily maintained. Resin curing is chemically activated. Once I add the hardener, I have 20 to 30 minutes to soak the crocheted cloth and finish draping. I apply colored resin to the cloth with a two-inch brush, making sure cloth is well saturated. I attach the wet cloth to the jig using screws or zip ties. After forms are fully cured and hard which takes 24 hours, with a Dremel tool, I cut along the sides that were attached to the jig, carefully carving out a clean interesting edge along the knots formed by the crochet. All edges and the front and the back of the form are hand sanded. One or two final coats of colored resin are applied to sanded forms and then I sand down any drips and touch up with resin on any sanded parts.  Laser-cut acrylic:

Laser-cut acrylic:

In 2016, I began using a laser cutter with an 18” x 24” bed, at the Fab Lab, a maker space at the University of Chicago. I was curious how my work with numbers would translate into this new material language. I began developing work using laser-cut acrylic sheets separated by vinyl spacers. Here, simple geometric shapes, panel placement, cut-outs, and engraved or drawn lines all plot numerical values.

To begin, I decide how numerical values will be interpreted or visualized, and choose a basic geometric structure to work with. In Photoshop, where one can change shape and color quickly, I run several sequences from either pi or e to determine form, commit to one, then try different color combinations. I tape the Photoshop sketches all over our living room. I pare down possibilities after hours or days of staring and walking by. The laser cutter I use works with Adobe Illustrator so I then create an Ai file for each component to be cut. I like to design three or four variations of the same system to laser cut all together. Before cutting, I prepare the acrylic sheets by replacing factory protective coverings with transfer tape in order to eliminate a haze the laser sometimes creates at the cut. Back in my studio, I work out the necessary hardware and assemble the final work.  Photography with laser-cut acrylic:

Photography with laser-cut acrylic:

All the crocheted fiberglass work is done in my home studio, so when I began working with the laser cutter outside of my home, my driving time increased greatly. Sitting in rush hour traffic, I began noticing Chicago’s geometry and then framing geometric abstraction in square and rectangular formats from the driver’s seat of my truck. I became obsessed with documenting patterns created by Chicago’s elevated train tracks and the shadows they cast on the street below.

I needed to develop an interesting presentation for an exhibition, based on concepts of borders and memory. As a sculptor, I needed to push these, just over the line, into the realm of sculptural objects, not simply framed photographs. Thinking about 35mm slides, photographs as records of inventory, the fact that iPhone image files limit possible print size, and that I am currently working with laser-cut acrylic, reference to film and slide mounts became the starting point of presentation for this project. To reference photographic film, images are printed on transparency film or clear acrylic sheet.

When you are looking for inspiration, what resources do you turn to?

Inspiration comes from learning a new material language and, of course, the math. I have recently begun learning the basics of frame loom weaving and collecting images with embroidery techniques. In January, I took a basic sewing class where I learned about various seam finishes. In these new experiences, I look for techniques that I can bring into the laser-cut acrylic work. Often, inspiration for a new series comes from its predecessor, as illustrated in the above laser-cut acrylic process description. In the summer of 2019, I participated in a residency and exhibition in central Bulgaria where I was able to bring the experience of a specific place and culture into the works. I hope to do that again.

I compile “art inspiration” folders on computer and phone, saving random images and screenshots on my computer from social media or newsletters and articles. These images give me a flash of an idea for technique, form, or color combinations that can be helpful for my creative process. These images are like visual notes that I run through, looking for just one act or characteristic to push new work into an unexpected direction.

Walk us through a typical day in your studio. What is your routine? Has it changed with COVID-19?

Typically I work in blocks of time spanning between one to ten weeks, where I focus on one type of task only. A block of time that focuses on the business of art: submissions, proposals, web updates, writing, art-related communications. A block of time for home bookkeeping and piles of filing that were ignored while working through the art business. These piles and Emails sit, sometimes for weeks or months, but not quietly. I clean up the desk and quiet the piles. Then, as my reward, I focus my energy solely on studio until a few pieces are completed. If I have a commission, the same ritual applies. Catch up on computer and desk stuff, then nothing but studio time until the commission is complete - working a full day (day and night), every day.

For years now, my life has been a series of sprints guided by deadlines, finishing one and off to chase the next. What COVID-19 changed is that because my spring events were canceled and the art world was put on pause, I gave myself permission to make repairs on my property, to not work after dinner, to not fight through fatigue, to clean and organize all of my workspaces.

The maker space where I use the laser cutter shut doors mid-March with no opening date in sight. I organized and took inventory of all the acrylic sheet scraps I had been saving since I started cutting with a laser. I bought a jigsaw. I dug up my old encaustic gear. I bought a sewing machine. I am inspired by people’s ingenuity in making PPE from whatever they have available. I want to bring this ‘make-do with what you have’ resourcefulness into my studio, using hand tools and materials from previous projects. Finding myself without access to laser cutter because of COVID-19, and a world on hold has given me the courage to just try stuff without the pressure of the new being good enough. What is your advice for combating creative block?

What is your advice for combating creative block?

I don’t really know what that means. For me, each finished body of work fuels a new series or investigation as a reaction to an aspect of the previous. There are so many creative doors that I want to open as a continuation of what I do now, that I always have a lane to explore. My advice would be to keep the hands moving. If you are stuck in your head, use your hands. Reconsider an older unfinished work and rework it with your current eyes. Activate the connection between the brain and the hand.

I do struggle to take the first step as I prepare to design a new system or feel the need to use a new tool or new technique. Taking the first step into the unknown is often overwhelming. I realize that the struggle is part of the process, that most if not all of us have these hurdles, and that this is a necessary single step or bridge that must be crossed. Recognizing that this is normal and that eventually, you will cross the barrier is somehow less oppressive. Just don’t stop.

As an artist, how do you measure your success?

Every time I finish a new body of work, I feel successful. Commissions make me feel successful. Selling existing artwork makes me feel successful. Every time I realize a new idea that results in a series, I feel successful. Success is engaging the viewer. Success is orchestrating a shared experience through my artwork. Success is not giving up. How do you see the art market changing? Where you do see yourself in this transition?

How do you see the art market changing? Where you do see yourself in this transition?

Not that long ago, we were mailing out slides with return envelopes, using addresses gleaned from paper publications. For a very short period, CDs with JPG images were the norm. Now, all submissions are online or Email. Postcards and even Email blasts are seldom used. With Facebook, Instagram, and art selling apps and websites, our access to resources, to industry, and to prospects is much more wide-reaching. One cannot interact with the art world fully without Facebook and Instagram accounts. But one aspect has not changed. Networks matter. Networks are essential. Attending gallery openings is still essential to create new relationships. Equally as important is a good Instagram routine to find and foster new opportunities. I wish I was better at both.

What advice do you have for artists who are beginning to build their careers? Have there been any habits or strategies that you have adopted that you feel have created more opportunities or visibility for your work?

Keep working. Get your work seen, outside of the studio. Fresh out of MFA school, I sought out calls for group exhibitions that spoke specifically to my work. I used submission deadlines as goals to create two or three new works. As soon as one application was out the door, I would find another call, make two or three new works, document, submit, and repeat. Project by project the work evolved and resume grew. As new works accumulated, I began applying for solo exhibitions in college galleries, art centers, and regional museums. I used these opportunities as carrots to work and evolve continually.

Being part of a network is invaluable. Build friendships in school. Keep in touch with significant mentors. Join a group, create your own with art friends you respect, collaborate. Failure is an inevitable part of success in any field. Do you have advice for overcoming setbacks?

Failure is an inevitable part of success in any field. Do you have advice for overcoming setbacks?

The art market is so lopsided and so skewed, making good art is just not enough to succeed, whatever that means. What others call failures and setbacks, we need to see as part of the art world process. Most often, setbacks contain an upside. Every submission rejection follows exposure to art professionals. Can’t get a gallery? Research and find alternate ways to sell your art. Discovery in one aspect of your practice will inevitably evolve the rest of your practice. Disaster in the studio? See it as a chance for innovation. When you look past a shut door, another can be kicked open, eventually.

What sparked your interest in partnering with TurningArt?

I appreciate that TurningArt has multiple ways of employing their artists. I admire the works and artists that they work with. I feel that they keep all aspects of my studio work in mind. So far, I have created a proposal for a new laser-cut acrylic piece; sold an existing crocheted fiberglass group; was considered for lease with older crocheted fiberglass pieces, and have received positive feedback from the team about the laser cut acrylic and photographic works. I feel that I can continue to evolve my work and TurningArt will always consider it when appropriate. Working with the TurningArt team, I feel like a partner. For all these reasons, I find this relationship rare and not to be taken for granted.

What does having your artwork in the workplace and other commercial or public spaces mean to you?

Making art is a personal journey, a personal challenge that, in the end, is meant to be shared. Art is a language. Its purpose is to communicate and to engage. To be heard and felt art needs an audience. Work displayed publicly becomes a shared experience. The difference between private and public collections is that of sharing and connecting with the few versus the many. I am proud of the work I make and want to share it. Public access allows greater opportunity to positively affect another human’s day, for a moment, to slow down, to calm, to make them feel connected to something, to create a shared experience. That is the power of art.

To see more featured TurningArtists, return to our blog. To get Yvette Kaiser Smith's art in your space, set up a free consultation with an Art Advisor here!

.jpeg?width=1500&name=IMG_8566_(2).jpeg)

.jpg?width=332&height=177&name=%E6%A9%983-2%20(1).jpg)